Welcome to Women’s History Month. This month, I pay tribute to the women in food, some celebrated, some unsung, who’ve inspired me at the keyboard and in the kitchen.

If you’ve been reading me for a while, you know Paula Wolfert has long been my culinary muse.

Before her, there was my paternal grandmother Marcella, for whom “the spirit of adventure came naturally.” When I was little, Marcella turned me on to halvah. “It was my gateway drug,” as I write in Feeding the Hungry Ghost. “From then on, I was always game to try new foods, and Marcella was happy to be my guide.”

I inherited Marcella’s big-hearted impulse to feed people. She got it from her mother Jenny and her aunt Minnie.

Jenny and Minnie came from Bohemia. Before it was shortened to boho and came to mean kinda artsy, kinda wild, Bohemia was an actual place in the Czech Republic. But it was being fought over to death during the First World War, and the sisters had to leave.

They might not have had so much as a coconut to cling to in this strange new country, but they had each other. Their English was dodgy, but they knew their way around a kitchen. So they cooked. Or rather, Jenny, the elder, did. She prepared the solid comfort food of eastern Europe, adapting it to American ingredients and American tastes.

Minnie didn’t have to adapt much. She baked, and Americans already liked butter and sugar just fine. She had a light touch with pastry, and among her specialties were jam cookies she topped with a latticework of lacelike fineness.

Together, the sisters ran a bakery, a bunch of coffee shops, and the kitchen at an inn.

Cooking was their living, but it was also their means of creating community, of making a home without a homeland. Everyone knew them and their bountiful cooking, their no-nonsense ways, their improvised English, their outsized hearts.

During the Depression, they’d accidentally-on-purpose leave a vat of soup and a flat of rolls by the back door when they’d lock up at night. Some people said the sisters’ food kept them alive.

Jenny was my paternal great grandmother, and by the time my father knew her, she’d suffered a stroke and could not speak. It didn’t stop her from cooking, though. She prepared the family meals until she died, which was long before I was born.

Minnie was still alive, though, when I came along. According to my parents, whenever we’d visit, I’d race inside and yell her name and barrel into the kitchen, which is always where she’d be, and throw my arms around her. She’d hug me right back and give me a cookie. I remember her scent of roses and butter and sugar.

Here’s what I don’t remember: she had only one arm. She’d lost the other to diabetes. But she still made her delicate jam cookies with one arm, hugged perfectly fine with one arm, and always beamed when she saw me, her old face suddenly young.

We had no common language other than love and cookies, but in these, she was fluent and plenty complete as far as I was concerned.

I have tried to cobble together information about Jenny and Minnie in the same way — to create a sense of wholeness despite great gaps in their history. We know they first settled in Chicago. Jenny married. At some point, her husband was instructed to move somewhere warmer for his health. So Jenny and Minnie pulled up stakes again, and all three of them came to Miami. It was more swamp than city then, and it couldn’t have helped her husband’s health too much. He died before my dad knew him.

Kierkegaard said life only can be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards. Living forwards is what Jenny and Minnie did. The sisters — both exiled, one widowed — did not complain. They cooked. They did not speak of the past; instead, they learned the ways of a new and different country, with new and different foods.

In Miami, those foods include coconut. Minnie’s coconut cake is one that family members still talk about with something akin to rapture. It is, for them, the taste of home.

As we talk and talk about immigration reform, what people forget is most of us didn’t come from here. We all came from somewhere else. I doubt that Minnie and Jenny would care who you are or what brought you to this country. You have come a long way to be here now. And you’re probably hungry.

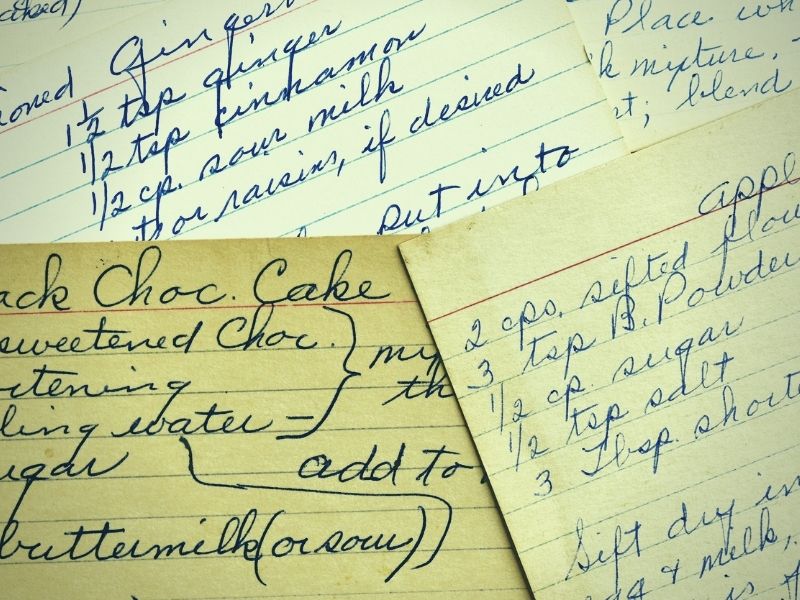

I have yet to veganize Minnie’s famed coconut cake — I haven’t had the nerve — but I’ve had success veganizing her fabulous cookies, a longtime family favorite. I sometimes wonder what Jenny and Minnie would have made of modern life and of me. They were mighty far from vegan. They’d have recognized my cast iron skillet, but God knows what they’d have made of a food processor. I bet they’d have loved it once they wrapped their heads around it. My food choices may be different from theirs, but the act of cooking and eating is eternal.

Save your family recipes. They, too, are part of history.

Loved this. Moving tribute! They’re very much alive!