My Favorite people, My Favorite Recipes: Yotam Ottolenghi

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to interview someone on whom I had a culinary crush. By that time, more than a few people felt that way about Yotam Ottolenghi, the innovative, exuberant Israeli chef who brought his bold flavors to London. We feverishly exchanged emails between London and Miami, yet despite the geographic distance, the interview had an easy intimacy. Since interviewing him for Culinate, Ottolenghi’s empire and reputation has only grown — five cookbooks, five restaurants, regular food columns in The Guardian and The New York Times and numerous awards. His family’s grown, too. With partner Karl Allen, he’s raising Max, 4, and Flynn, 2.

Caveat — he’s — gasp! — not vegan. But he’s got a way with vegetables that makes even omnivores want them, and that to me is the bigger win. Ottolenghi’s vegan version of makloubeh, — Arabic for upside down — coaxed me into the kitchen. Could I magically recreate this one-pot meal of vegetables, rice and spices or would it be a hot — though delicious — mess? No worries — another thing about Ottolenghi — his recipes work. I still have a culinary crush on him as he continues to lavish love and tahini on all vegetables.

Yotam Ottolenghi

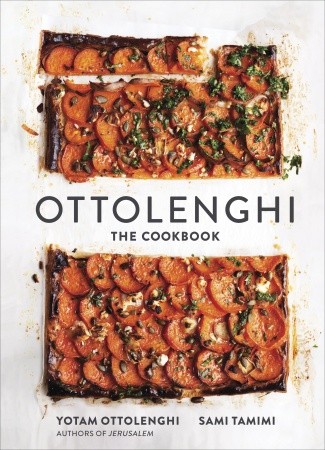

Once upon a time in Jerusalem, Yotam Ottolenghi was a philosophy and literature student destined to follow his father’s footsteps into academia. He moved to London to pursue a Ph.D., but took a detour through the kitchen via the Cordon Bleu cooking school. Scholarly life lost out. The truth is, Ottolenghi had always been more excited by his Italian father’s culture and cuisine than he was by comparative literature. In 2002, Ottolenghi and his business partner, Sami Tamimi, opened Ottolenghi, their London shop/deli/bakery, serving exuberant interpretations of Mediterranean classics. There are now four Ottolenghi locations throughout the city, and Ottolenghi-Tamimi fever has spread abroad with their cookbooks Jerusalem (the wildly popular winner of the IACP’s 2013 Cookbook of the Year Award), and the earlier Plenty, which so celebrated and glamorized vegetables that people took Ottolenghi to be a vegetarian visionary (he’s a happy omnivore). Now, a decade after its original UK release, Ottolenghi: The Cookbook has finally made it to America.

Once upon a time in Jerusalem, Yotam Ottolenghi was a philosophy and literature student destined to follow his father’s footsteps into academia. He moved to London to pursue a Ph.D., but took a detour through the kitchen via the Cordon Bleu cooking school. Scholarly life lost out. The truth is, Ottolenghi had always been more excited by his Italian father’s culture and cuisine than he was by comparative literature. In 2002, Ottolenghi and his business partner, Sami Tamimi, opened Ottolenghi, their London shop/deli/bakery, serving exuberant interpretations of Mediterranean classics. There are now four Ottolenghi locations throughout the city, and Ottolenghi-Tamimi fever has spread abroad with their cookbooks Jerusalem (the wildly popular winner of the IACP’s 2013 Cookbook of the Year Award), and the earlier Plenty, which so celebrated and glamorized vegetables that people took Ottolenghi to be a vegetarian visionary (he’s a happy omnivore). Now, a decade after its original UK release, Ottolenghi: The Cookbook has finally made it to America.

In an email conversation from his home base in London, Yotam Ottolenghi talked about his favorite subjects, his infant son Max, social media, local food, and okra.

In an email conversation from his home base in London, Yotam Ottolenghi talked about his favorite subjects, his infant son Max, social media, local food, and okra.

Italian father, German mother, Israeli childhood, London restaurant and home. What dish tastes like home to you? A difficult question. I guess I have quite a few “homes” now, in reality or in my head. Roasted chicken with thyme and lemon that Karl, my beloved partner, often cooks is definitely one home. My mother’s cilantro mayonnaise is another. A dish of warm hummus topped with fava beans and lemon juice is home; so is platter of butternut squash with yogurt and chile à la Ottolenghi.

In Ottolenghi: The Cookbook, you joke if you don’t like lemon or garlic, turn to the last page. I love your embrace of flavors — lemon, garlic, saffron, cumin, preserved lemon, olives, pomegranate molasses, za’atar. These spices, herbs, Mediterranean flavors and textures, the whole grains, the produce — these have all been around for centuries. And yet you and Sami Tamimi seem to have introduced them in a whole new way. How did you go about doing that? There was no consciously planned strategy. These are the ingredients which excite us, which we know and love to cook with and eat. Our toolbox, as it were, has perhaps coincided with a time when people’s receptiveness to new and so-called “exotic” ingredients is growing all the time.

As you say, these products have been around as the daily staples of millions for centuries. The hard work has been done: we are just having fun spreading the word! Word-of-mouth and social media is also a really exciting thing to witness. Someone “discovers” an ingredient, gets excited about it, tweets about it, and suddenly it’s being sought all over and being experimented with in new ways.

How did the British, with their culinary history of bland, beige, and boiled, initially react to your cooking? How has England’s food sensibility changed since then? Brits have always had a tough time of it, reputation-wise. There were certainly splashes of color in the culinary palate before we arrived. A lot has changed, though, since we started out over a decade ago, when sun-dried tomatoes were considered the apex of culinary exoticism. Our focus on the market was targeted from the outset, and our customers have always responded enthusiastically to our food.

In terms of the home cook, it’s taken longer to break through. There will always be the “meat and two veg” kind who will bemoan the lack of gravy and the need to seek out some ingredients. But, generally, the reaction has been pretty delightful from the outset.

How does an English food sensibility differ from an Italian one? From an Israeli one? The English are more open to new flavors than most nations I know. They are less patriotic about their own food. As a result, the British food scene is dynamic, and encompasses foods from all corners of the world, quite literally.

As we become more globalized, what do you see happening with regional cuisine? Are we at risk of losing it? What are the consequences of that? I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive. Yes, it’s amazing to live in a city and be able to eat through the foods of the world in the course of one day. But, at the same time, nothing tastes better than when food is cooked and eaten when and where it was grown and when it is meant to be eaten. Fish tastes better when you can see the sea. Cox apples don’t taste right unless it’s fall. Asparagus is incongruous on Christmas Day.

I think people are able to straddle these two stools without falling in between — to visit a local supermarket and the small specialist local farmer’s market together on the same day.

You opened Ottolenghi in 2002. How has your approach to food evolved since then? Some things have changed. A few new ingredients and methods are now a key part of our day-to-day cooking, and I’m much more inclined towards Asian cooking that I was at the outset. But so much has stayed the same.

Reading back on the first publication of our first cookbook, the vision and priorities laid out by Sami haven’t really changed at all. It feels good to see we haven’t swayed in this regard. Perhaps I’m more relaxed and experimental than I was in 2002, more prepared than ever to turn a recipe on its head and see how it looks.

What about changes to your palate? Are there flavors, textures, or ingredients you favor now that you didn’t appreciate before? There is much more of an Asian influence in my cooking than there was at the beginning. This is the result of traveling in the region, and also the influence of working with our head chef, Ramael Scully. There would be a lot less star anise, miso paste, soy sauce, and ginger in our cooking if it were not for Scully.

Do you ever try to develop a recipe that got away, a flavor or a texture you wanted but couldn’t nail? What about dishes the kitchen thought would be a smash that didn’t work for patrons? It’s rare for us to completely shelve a recipe we are developing. About one in every 20 get put to one side, I’d say. With two or three testings, we generally get to a really good place with a recipe, even if it’s very different from the initial vision.

What was recently meant to be a chickpea sauce for linguine turned out to be a very moreish spread on toasted sourdough. A creamy potato-and-tuna salad I made this summer came about from a “failed” attempt to make tuna confit by slowly cooking the fish in oil; I ended up with something not much better than a decent can of tuna. A few ingredients were added, and it turned into a take on salade Niçoise with a creamy, tuna-based sauce similar to the one used in the classic Italian dish vitello tonnato.

Some things don’t work — trying to re-create a cake eaten in a little village in Greece made me see that most cakes really do need eggs — but, generally speaking, there are very few straight-in-the-bins.

What makes a recipe bookworthy? For a recipe to be bookworthy, it needs to work, and it needs, I think, to be a little bit different: it needs to challenge and comfort at the same time. There will always be some dishes which I am crazy about that pass without too much fanfare; I’m not sure anyone was quite as evangelical about my buttermilk-encrusted okra as I was a year or so ago. (Aaah, the blindness of a parent towards the favored child!) But more often than not, it works the other way, with dishes I think are very simple, straightforward, and “unremarkable” becoming the smash hits.

Congratulations on Jerusalem winning the IACP’s Cookbook of the Year Award. Much has been made of your partnership with Sami Tamimi. Do you ever feel like the poster boys of Arab-Israeli conflict? Does it ever threaten to eclipse the food itself? Does it create a sense of responsibility? Would you rather we just shut up and eat? Aaah, were we all just to “shut up and eat,” as you say! But what would we talk about over supper?! Our day-to-day is all about the food itself — making the best food and developing new recipes for our customers — so, no, we don’t feel like poster boys. But, however irreverent and food-focused we’d like to keep it all, there is of course a sense of responsibility when asked to talk about the conflict.

How does your style in the kitchen differ from Sami’s? Our cooking styles are pretty similar, to be honest. Sami spends more time in the restaurant and deli kitchens, mentoring and developing our team of young chefs, so he’d certainly win the “who can chop an onion faster” competition. But, generally speaking, our palates and ideas about what food should look and taste like are pretty much aligned.

Your cooking, your Guardian column, and Plenty_ have given produce the star treatment it deserves. What meatless dishes do you turn to for comfort? My ultimate comfort-food dishes? It’s a toss-up between a shakshuka brunch, brown rice with miso vegetables for lunch, or — can anything beat some simple fresh pasta with a homemade tomato sauce for supper?

How has your son, Max, influenced you in the kitchen? What is he eating? He’s made me worry that we need a second fridge. He’s 8 months with an appetite of an 8-year-old. He eats what we eat, just more of it.

How would you feel about him cheffing? I can’t imagine the little guy walking yet, so I haven’t gotten around to imagining his future career. On my 40th birthday, my father said he was delighted, with hindsight, that I never listened to his advice enough to actually follow it. I hope that Max one day says the same.

Vegetable makloubeh

This centrepiece dish, popular in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, normally includes chicken or mutton, rice and lots of vegetables, and is served with yogurt or tahini. This strictly vegetarian version is as wholesome as the original, though. Sami remembers his mother bringing the makloubeh pot to the table and turning it over in front of the children's eyes. She would then cover the pot with a tea towel and ask the kids to stroke it gently to "help the makloubeh come out whole", before briskly lifting it away; a dramatic effect perfect for a vegetarian Christmas. You'll need a big, heavy-based pot with a five-litre capacity (23-25cm in diameter, 12cm, or less, deep) and a plate or platter big enough to cover the pot - the plate will be used for unmoulding the rice, much as you do with a pudding.Ingredients

- 200 ml vegetable oil for frying

- 1 large aubergine cut lengthways into 0.5cm thick slices

- 2 medium potatoes peeled and cut into 0.5cm slices

- 1 small cauliflower cut into large florets

- 2 medium carrots cut lengthways into 0.5cm thick slices

- 2 large tomatoes cut into 1cm thick slices

- 4 garlic cloves peeled and sliced

- 200 g short-grain rice risotto or paella rice, washed and drained

- FOR THE LIQUID:

- 400-500 ml vegetable stock or water

- ½ tsp ground turmeric

- 1 tsp paprika

- 1 tsp ground nutmeg

- 1 tsp ground cardamom

- 1 tsp black pepper

- 2 tsp salt

- FOR THE TAHINI SALAD:

- 80 ml tahini paste

- 80 ml water

- 40 ml lemon juice

- 1 garlic clove crushed

- 1 tbsp dried mint

- 15 g flat-leaf parsley chopped

- Salt to taste

- 4 medium ripe tomatoes cut roughly into 2cm cubes

- 4 mini-cucumbers or 1 large one, deseeded, skin on, cut roughly into 2cm cubes

- olive oil

- 10 g mint leaves roughly chopped

Instructions

Such appealing recipes, Ellen! If I didn’t have a broken arm, I’d try them immediately. Right now just trying to figure out how to cut up an onion with only one working hand. Hmmmmm….

Keep up the good work!

Anna

Oh, my goodness, Anna. I hope someone’s making you magloubah or otherwise caring and feeding for you. You need your arm. Feel better, wonderful friend.